Click here to view our collection of paintings

Watercolour is the simplest and oldest way of applying paint; Paleolithic cave paintings were probably made with some form of pigment suspended in water, and watercolour has also been used for the illustrations in manuscripts of various kinds – although, as with frescoes, tempera (that is, paint on a base of egg yolk) was also used. Albrecht Dürer’s (1471-1528) studies are generally thought to be amongst the earliest finished watercolour paintings, as free-standing works of art in their own right. As well as the famous Great turf and the Young hare, there are other highly-finished and exquisitely refined botanical paintings, (Aquilegia, Buttercups & red clover), animals (a deer’s head, a cow’s nose, squirrels) and insects (a stag beetle), landscapes and figure studies. Dürer’s legacy was a school of watercolourists established amongst his followers which helped to diffuse the practice, although for most artists watercolour was the first stage in a work, useful for sketches, studies and cartoons. Botanical drawings remained the most popular and consistently practiced branch of the art until the 18th century.

Watercolour is the simplest and oldest way of applying paint; Paleolithic cave paintings were probably made with some form of pigment suspended in water, and watercolour has also been used for the illustrations in manuscripts of various kinds – although, as with frescoes, tempera (that is, paint on a base of egg yolk) was also used. Albrecht Dürer’s (1471-1528) studies are generally thought to be amongst the earliest finished watercolour paintings, as free-standing works of art in their own right. As well as the famous Great turf and the Young hare, there are other highly-finished and exquisitely refined botanical paintings, (Aquilegia, Buttercups & red clover), animals (a deer’s head, a cow’s nose, squirrels) and insects (a stag beetle), landscapes and figure studies. Dürer’s legacy was a school of watercolourists established amongst his followers which helped to diffuse the practice, although for most artists watercolour was the first stage in a work, useful for sketches, studies and cartoons. Botanical drawings remained the most popular and consistently practiced branch of the art until the 18th century.

British watercolours grew out of this scientific use of the art, which also encompassed map-making, topographical drawing, and the use of watercolour on expeditions for recording details of the land, fauna, flora, people and customs. By the 18th century artists such as Elizabeth Blackwell (illustrator of a 1738 herbal for Sir Hans Sloane), Paul Sandby (employed by the Surveyor-General of the Ordnance to map Scotland in 1747) and later Thomas Malton (topographical artist and teacher) were working in the medium, and contributing to its growth as the best means of recording military surveys, the topography of the great estates, and scientific discoveries. Sir Joseph Banks and other members of the Society of Dilettanti were great patrons of the watercolourist, for botanical, geographical and archaeological record. The use of watercolour leached into the leisure practices of these artists; Sandby painted views of Scottish landscapes and events he witnessed, and the influence of landscape painting in oils via the strong Dutch tradition combined with this more realistic, non-functional approach to watercolour to create a flourishing school of landscape artists.

Besides the scientific genre of watercolour painting, there was a strong amateur inclination which supported its development. It became a recognized accomplishment in the mid-18th century for well-born young people of both genders, and their teachers were often noted practitioners, such as Alexander Cozens. With the growth in interest in the concept of the ‘picturesque’, the countryside became a place in which to journey, to experience and record the sublime, rather than a place of wilderness and terror to be fenced out behind the walls of an estate. William Gilpin, J.R. Cozens and Gainsborough all contributed to this journey towards the romantic in landscape painting, whilst Rowlandson, as well as partaking in it, also satirized it. Gainsborough also adapted the Dutch genre of peasant life, rural landscapes of fêtes and winter sports to the English countryside, enlarging a tradition of cottage views, rutted roads, carts and churches seen through trees, to which Rowlandson had also contributed.

Turner and Thomas Girtin, nourished on the work of the previous generation, invested it with a grandeur and sublimity which gave it the dignity of an oil painting; Girtin died young, but Turner’s long and prolific life took the practice of British watercolour painting to a new and dramatic level. Collectors of watercolours had increased during the 18th century; now there were patrons (such as Walter Farnley) who would hang a whole salon with their collection of Turner’s watercolours. In 1804 the Society of Painters in Watercolour was founded, and although this brash upstart was not thought of as having much chance of lasting, in comparison with the Royal Academy (founded 1768), it survives even today as the Royal Watercolour Society. Turner gave equal weight to the exhibition of his watercolour works as his oil paintings, and by the 1830s the production of ‘exhibition watercolours’ – as finished and considered as oil paintings – was thoroughly established.

The 19th century saw the growth of watercolour in every genre of painting, including history and subject paintings, portraits and orientalist works. The rapid growth of a middle and lower middle urban class, with an appetite for decorating their homes in imitation of their wealthier countrymen encouraged an increasing trade in smaller, less expensive, and more cheaply frameable pictures, including prints and watercolours; for women, too, watercolour painting had since the mid-18th century been seen as a suitable accomplishment, and in the 19th century became an occupation. Helen Allingham and Kate Greenaway, for instance, both born in the 1840s, were extremely successful, both critically and financially, and are seen now as hugely collectable.

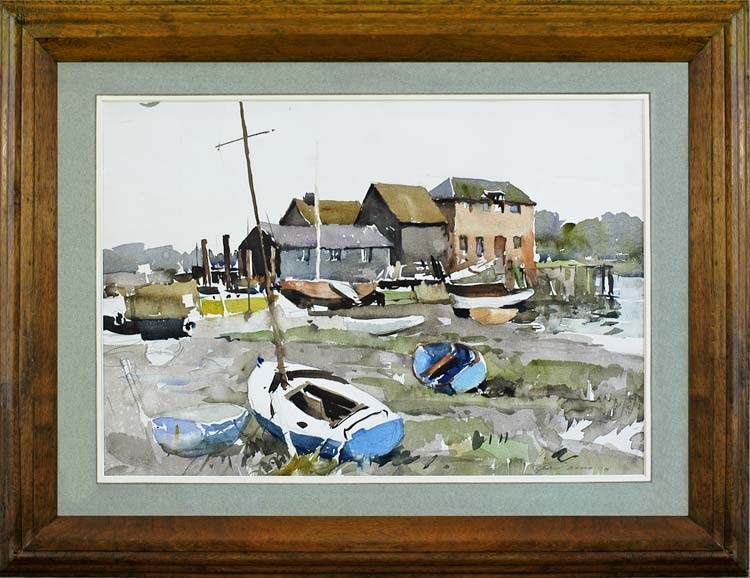

The large number of hobby watercolourists in Britain has always seen a migration between amateur and professional painters, and still today this is one of the more permeable branches of fine art. Edward Wesson, for example, although self-taught and disparaging of art schools, himself taught formal art courses as well as giving demonstrations to provincial art societies. He became widely known throughout the country through this practice, and his own lack of training did not prevent his belonging to the Royal Institute of Painters in Watercolour, or in exhibiting at the Royal Academy and elsewhere.